The Effects of PFAS in Drinking Water

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) have become a major public concern in drinking water around the world. Sometimes referred to as “forever chemicals,” PFAS are a large class of man-made compounds used for decades in products designed to resist heat, water, oil, and stains. These PFAS include items such as non-stick cookware, waterproof textiles, food packaging, and firefighting foams. Because of their widespread use and persistent nature, PFAS have made their way into soil, air, food, and our water supplies, including municipal and private drinking water sources, according to the EPA.

Understanding what PFAS are, how they enter drinking water, and what their potential effects are is important for public awareness about water treatment and policy.

This post provides an evidence-based overview of PFAS in drinking water and summarizes current research findings and regulatory context.

What Are PFAS?

PFAS stands for per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, a family of thousands of synthetic chemicals characterized by strong carbon-fluorine bonds that resist degradation in the environment. Because of their durability, PFAS do not break down easily in soil, water, or living tissues, which has led to their accumulation in the environment and in humans over time.

Some of the most studied PFAS compounds include perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS). Although production of these specific chemicals has been phased out in the United States, they continue to be detected in environmental media and human blood.

Because there are thousands of PFAS compounds, assessing their combined presence and effects remains complex and challenging for scientists and regulators alike.

How PFAS Enter Drinking Water

PFAS can enter drinking water systems through a variety of pathways:

- Industrial sites. Facilities that manufacture or use PFAS can release these chemicals into nearby waterways or groundwater.

- Firefighting foam. Aqueous film-forming foams (AFFFs) used at airports, military installations, and fire training facilities often contain PFAS, which can infiltrate soil and groundwater.

- Consumer product disposal. PFAS from landfills, wastewater treatment plant effluent, and surface runoff can transport these compounds into water sources.

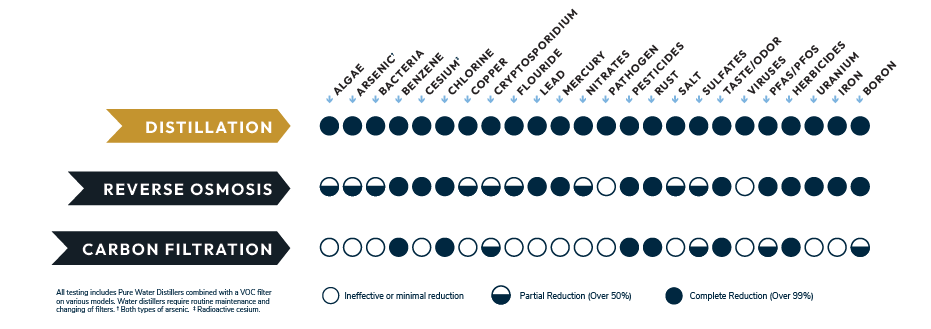

- Environmental persistence. PFAS do not degrade easily, so once they enter the environment, they can remain for long periods, potentially reaching drinking water supplies. There is no known way to break these substances down, only Distillation can truly remove PFAS from water.

In some regions, testing has detected PFAS in a significant portion of drinking water systems, highlighting the widespread nature of this issue.

PFAS in the Human Body

Once PFAS enter the drinking water and are ingested, they can be absorbed into the bloodstream. Many PFAS compounds are known to persist in the human body for years. Some research suggests that these chemicals accumulate over time, meaning that long-term exposure, even at low levels, can contribute to measurable body burdens of PFAS.

Blood tests can detect PFAS exposure, but available tests cannot predict whether a person’s exposure will lead to specific health outcomes.

Major Areas of Health Research

PFAS are one of the most studied classes of contaminants in environmental health science. Regulatory agencies like the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), public health departments, and scientific bodies have reviewed hundreds of studies to understand possible health effects. Although research continues and some findings vary depending on the specific PFAS compound, several health outcomes have been repeatedly examined in human and animal studies.

1. Developmental Effects and Birth Outcomes

Research has found associations between PFAS exposure and outcomes such as low birth weight, pre-eclampsia (a condition involving high blood pressure during pregnancy), and other developmental effects. For example, one human study indicated that PFAS exposure was associated with preterm births and lower infant birth weight in communities with contaminated well water.

Children may be especially sensitive to exposure during critical periods of growth and development, but more research is needed to clarify specific mechanisms and thresholds.

2. Immune System Effects

Several scientific studies have identified potential impacts of PFAS on the immune system. Specifically, some PFAS exposure has been linked with reduced vaccine response in children — meaning that the immune system produces fewer antibodies in response to immunizations.

Other research indicates that immune effects may include changes in immune cell function, though results can vary depending on the compound and exposure level. ATSDR

3. Hormone and Metabolic Effects

PFAS have been studied for potential effects on hormone regulation, particularly thyroid function. Some research suggests associations with thyroid disease and changes in cholesterol levels, though the evidence is complex and not fully conclusive.

Long-term exposure has also been linked with metabolic outcomes, such as changes in lipid metabolism or insulin regulation, which may intersect with health issues like Type 2 diabetes.

4. Cancer Risk

Associations between PFAS exposure and certain types of cancer have been reported in several studies. For example, PFOA exposure has been linked to increased risk of kidney and testicular cancers in communities with documented contamination.

Recent research exploring broader cancer incidence patterns has also suggested associations between PFAS in drinking water and cancers in the digestive, endocrine, and respiratory systems, though additional studies are necessary to confirm these findings.

5. Liver Effects

Animal and human studies have identified potential impacts of PFAS on liver function. These may include changes in liver enzymes and alterations in lipid metabolism, which could indicate stress on liver processes.

Interpretation and Scientific Context

It is important to recognize that association does not prove causation in many studies. That means while researchers have observed links between PFAS exposure and certain health outcomes, the presence of PFAS alone does not guarantee that an individual will develop a particular condition. Many factors, including genetics, overall environmental exposure, lifestyle, and underlying health, influence individual risk.

Regulators and scientific bodies continue to review and update their understanding as new research becomes available. Ongoing research aims to provide clearer insights into dose-response relationships and long-term effects at exposure levels commonly found in drinking water.

Regulatory Landscape

In recent years, regulatory agencies have taken steps to address PFAS in drinking water. In the United States, the EPA finalized a national primary drinking water rule for several PFAS compounds, establishing maximum contaminant levels (MCLs) to protect public health. These actions are intended to reduce exposure and associated risks over time.

Different states have also adopted their own PFAS standards and guidance levels, often setting benchmarks for individual PFAS or groups of related compounds that reflect local conditions and scientific assessments.

Despite these regulations, PFAS continue to make their way into drinking water and pose a threat to the health of people everywhere. Would you rather have water that has a limit on how many PFAS can be in it, or have drinking water that has zero PFAS in it?

What This Means for Drinking Water

PFAS contamination concerns highlight the importance of comprehensive water quality testing, comprehensive treatment strategies, and public awareness in decision-making about drinking water safety. Because PFAS do not have taste, color, or odor in water, testing is the only reliable way to confirm their presence and concentration.

Communities with known PFAS contamination, especially near industrial sites or other PFAS sources, may consider a range of options to reduce exposure, including advanced water treatment technologies. Some treatment methods, such as granular activated carbon, ion exchange, or high-pressure membranes like reverse osmosis, can be effective at reducing certain PFAS concentrations in drinking water, though effectiveness varies by compound and system design.

Our Pure Water Distillers have been third-party tested and have proven to consistently remove over 99.9% of PFAS.

What to Do Now

PFAS in drinking water represent a complex environmental and public health issue. These persistent chemicals can enter water supplies through industrial and consumer pathways and have been detected in many water systems. Scientific research has found associations between PFAS exposure and a range of health effects, including developmental impacts, immune system changes, hormone disruption, liver effects, and increased risk of certain cancers.

Because PFAS comprise a large class of chemicals with varying properties and effects, ongoing research and regulatory efforts are critical. Continued monitoring, updated scientific understanding, and evidence-based water treatment and policy responses remain key in taking steps to reduce PFAS in drinking water.

Take Action

The optimal way to remove PFAS and other contaminants from your water is through distillation. Pure Water Distillers has established credibility for consistently removing PFAS from drinking water, 99.9% of PFAS to be exact. Because distillation heats water to create steam and separates the steam (pure H2O) from the contaminants left behind, it is consistent in removing PFAS in every cycle. Are you ready to make the switch and get pure, clean water in your own home?

Order your own Pure Water Distiller today!

Good article. Are you going to make a pamphlet?