Pesticides in Drinking Water: What is the risk?

When most people hear “pesticides,” they think about farms, lawns, or produce. But pesticides can also show up in the water sources that communities and private wells rely on. Pesticide contamination is a real, documented pathway that’s worth understanding, especially if you live near agriculture or use a private well.

This guide breaks down (1) how pesticides get into drinking water, (2) what “danger” means, (3) which pesticides are most commonly detected, and (4) practical steps you can take to reduce exposure.

What counts as a “pesticide,” and why it matters for water

“Pesticide” is a broad category that includes herbicides (weed killers), insecticides (bug killers), fungicides, and other compounds used to control pests. Different pesticides behave differently in the environment. Some break down quickly. Others can persist longer, dissolve into water, or attach to soil particles and travel during runoff.

From a health perspective, the potential effects of pesticides depend on the specific chemical, the dose, and the duration of exposure. The EPA notes that some pesticide classes (like organophosphates and carbamates) can affect the nervous system, while others may irritate skin/eyes or have other toxicological concerns depending on the compound.

The key idea: risk is about exposure, not just detection.

How pesticides end up in drinking water

How pesticides end up in drinking water can be described in several ways. Pesticides can contaminate drinking water supplies, including movement from areas where they’re applied (farms, gardens, lawns) into surface water (rivers/lakes) or groundwater (aquifers).

Common pathways include:

1) Runoff after rain or irrigation

When pesticides are applied to fields or lawns, rainfall and irrigation can carry them into ditches, streams, and reservoirs, especially if application timing aligns with storms.

2) Leaching into groundwater

Some pesticides can move downward through soil and reach groundwater, depending on soil type, geology, and the chemical’s properties.

3) Seasonal spikes in surface waters

Monitoring programs often observe higher detections during certain times of year (for example, after agricultural application seasons).

USGS research consistently finds pesticides and their breakdown products in streams and groundwater, often as mixtures, not single chemicals. In one USGS summary, common herbicides and degradates appeared frequently, and shallow wells in agricultural and urban areas often contained multiple pesticides/degradates.

The “danger” question: detection vs. health risk

Today’s laboratories can identify pesticide residues in water at small concentrations, sometimes down to parts per trillion. Although the presence of a pesticide does not automatically mean there is a health risk, research shows that some pesticides, particularly with repeated or long-term exposure, may affect neurological function, endocrine activity, or other physiological systems, depending on the compound and exposure level. For this reason, health agencies use toxicity benchmarks to evaluate whether detected levels in drinking water may represent a potential risk over time.

How standards work for public water systems

In the U.S., regulated contaminants in public drinking water fall under the EPA’s National Primary Drinking Water Regulations (NPDWR). These rules include enforceable limits called Maximum Contaminant Levels (MCLs) for many contaminants. EPA also defines MCLGs (goals), which are non-enforceable public health targets set with a margin of safety.

Not every pesticide has an MCL. Some have health benchmarks or advisories, and some may be monitored under specific programs. That’s why it’s helpful to think in tiers:

- Regulated pesticide with an MCL → your water system must meet that enforceable limit.

- Unregulated pesticide with a benchmark → detection can be evaluated against health-based screening values (not the same as an enforceable standard).

- Emerging or less-studied chemicals → may have limited drinking-water-specific guidance, even if there’s broader toxicology literature.

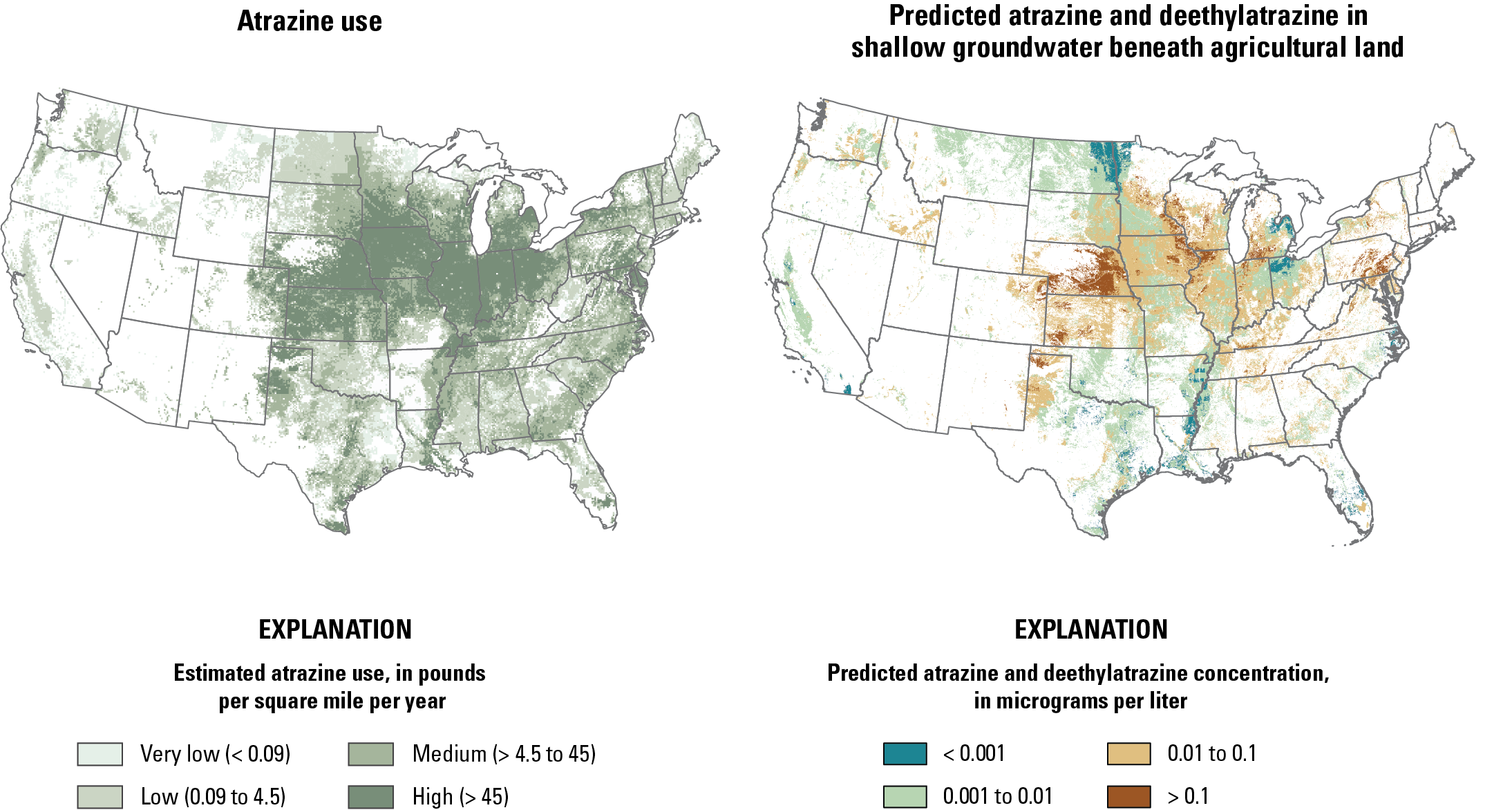

A concrete example: atrazine

Atrazine is a widely used herbicide and is one of the more commonly detected agricultural pesticides in water monitoring studies. ATSDR notes that EPA has set a maximum amount allowable in drinking water of 3 µg/L (0.003 mg/L) for atrazine.

You don’t need to memorize numbers; just know that when you see a pesticide listed in your local report, you can compare the detected level to the relevant standard/benchmark.

Which pesticides are most commonly found in water monitoring?

Across national monitoring, USGS has repeatedly reported common detections of herbicides (and their breakdown products) such as atrazine, simazine, metolachlor, and others, often appearing together as mixtures.

Urban streams can show different profiles (often reflecting lawn and structural pest control use), while agricultural areas tend to show a higher frequency of farm herbicides and their degradates.

Mixtures matter because real-world exposure is rarely “one chemical at a time,” even when each compound is present at low levels. That said, mixture risk assessment is complex, and the most practical consumer approach is still: identify what’s detected and reduce exposure.

How to find out if pesticides are in your drinking water

If you’re on city water (a public water system)

Start with your Consumer Confidence Report (CCR), the annual water quality report your utility provides. EPA sets requirements for these reports and explains what they must include.

What to look for:

- A table listing contaminants detected (often with units like µg/L)

- The MCL (or other reference value) and whether your water met the standard

- Source water information (river/reservoir vs. groundwater)

- Notes on seasonal monitoring or compliance

If you’re on a private well

Private wells generally are not regulated the same way as public systems. It is estimated that more than 23 million U.S. households rely on private wells. The CDC recommends testing well water at least annually for baseline indicators and working with your local health department to decide what additional chemicals to test for based on your area (including potential pesticide concerns).

Practical tip: if you live near cropland or have reason to suspect pesticide use nearby, ask a state-certified lab about a targeted pesticide panel that matches local usage patterns.

Reducing exposure: what actually helps

The question arises: Is any amount of pesticide really okay in your drinking water? While there are limits, they do not change the fact that these chemicals can be harmful to one’s health and pose potential risks when consumed.

There’s no one-size-fits-all solution, because “pesticides” are a broad group, but these steps are recommended:

1) Reduce the likelihood of contamination at the source

- Follow label directions for any home/lawn pesticide use

- Avoid applying before heavy rain

- Maintain buffer zones near wells, drainage ditches, and waterways

(These are prevention steps—especially important for private well owners.)

2) Choose treatment

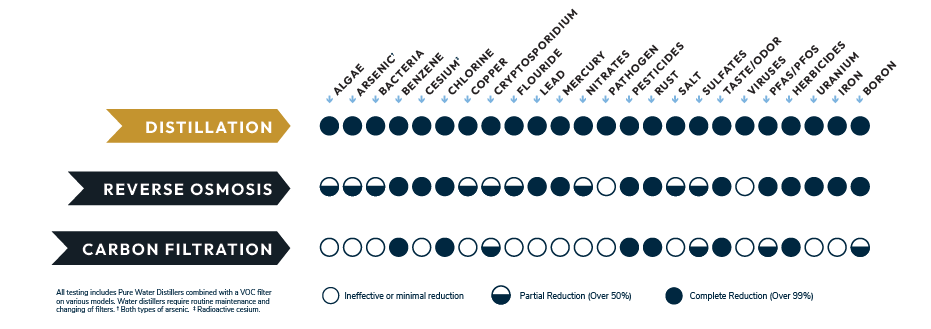

For many pesticides (which are often considered synthetic organic chemicals), activated carbon filters are widely used in drinking water treatment, but do not combat the issue on their own. The only tried and true method is Vapor Distillation. With a Pure Water Distiller, you will have a 99.9% removal rate of most pesticides. Distillation provides peace of mind that what you’re drinking is truly safe for you and your family to consume.

What this means for a pure water routine:

- Distillation is a strong foundation for reducing many dissolved contaminants.

- For pesticides that are volatile or semi-volatile, pairing distillation with an appropriate post-treatment carbon stage (when applicable) can add another layer of protection by adsorbing certain organic chemicals.

(If you’re selecting any treatment method, the most defensible approach is always: match the technology to the contaminants you’re targeting and rely on verified certification/testing data.)

An action plan

- Check your CCR (public water) or schedule well testing (private well).

- If pesticides are detected, identify the specific names and levels (e.g., atrazine, simazine).

- Compare results to EPA standards/benchmarks where available.

- Choose a treatment strategy aligned to your situation:

- Activated carbon (often used for Volatile Organic Compounds)

- Distillation (strong for many contaminants)

- Pure Water Distillers use both distillation and activated carbon filters to provide the purest drinking water

- Pitcher filters (can be effective at removing some pesticides, but effectiveness varies greatly by brand and chemical)

- R.O. (can be effective at removing some pesticides,

The promise of purity

Pesticides in drinking water are a legitimate concern when they enter water sources through runoff and groundwater movement. Also, they are frequently detected in national monitoring, often in mixtures.

At the same time, detection alone doesn’t equal danger; what matters is the level, the toxicology of the compound, and how you can limit exposure.

If you want to build a pure water routine at home, start with knowledge (your report/testing), then choose a purification method with verified, consistent equipment, and remember that different methods have different strengths and limitations.

Don’t let someone else decide what is “Good enough”; choose Purity and purchase a Pure Water Distiller today!

Leave a Reply